A few months ago, I discussed with a friend the subtle differences between writing by hand and typing on a keyboard. Since then, I've gradually returned to using notebooks and pens for taking notes. I don't even have the feeling of "reclaiming" handwriting because I never really started. Since getting my first laptop in high school, I've barely done any extensive handwriting.

This reminded me of an evening several years ago when I was driving my mother and several aunties who raised me back to their hotel after dinner. They had been with me throughout my childhood, so our conversation naturally drifted back to those early years. Before I started school, I spoke Taiwanese fluently—the native language spoken by the majority of Taiwanese people. But once I entered elementary school, the educational environment heavily favored Mandarin Chinese, which had become Taiwan's official language after 1949. Whether due to the school system or because my classmates primarily used Mandarin, my Taiwanese gradually deteriorated.

"Are you a mainlander's kid?" a relative who only spoke Taiwanese would often joke with me. This "joke" gradually spread among the family. In Taiwan, "mainlander" (外省人) refers to those who migrated from China around 1949 and their descendants—a group historically associated with Mandarin dominance and, in some contexts, a different cultural identity from native Taiwanese. To be mistaken for one while being ethnically Taiwanese carried subtle social implications. She meant no harm and was just joking, but over time I became increasingly reluctant to speak Taiwanese, and even avoided visiting that relative's home because within a few exchanges, there it was again: "mainlander's kid."

From that point on, my Taiwanese never improved.

Of course, my English wasn't much better either. Fortunately, as I grew older, I had a tutor who made learning interesting, and eventually my English reached a level where I could at least communicate. This made me realize that languages can actually be learned. Now I've started learning Japanese again—it's difficult, but I feel like I'm slowly making progress.

Besides my poor Taiwanese, another thing that was frequently mentioned was my "terrible handwriting." So after getting my first personal laptop in high school, I subconsciously avoided handwriting altogether. From then on began a two-to-three-decade life of typing out all kinds of notes and articles on keyboards. Typing has become an internalized way of thinking—a method of dialogue with myself that unfolds gradually with consciousness.

But after years of research into note-taking and writing, many people have mentioned the impact of handwriting with pen and paper on thinking. This is why I've reconsidered using pen and paper again.

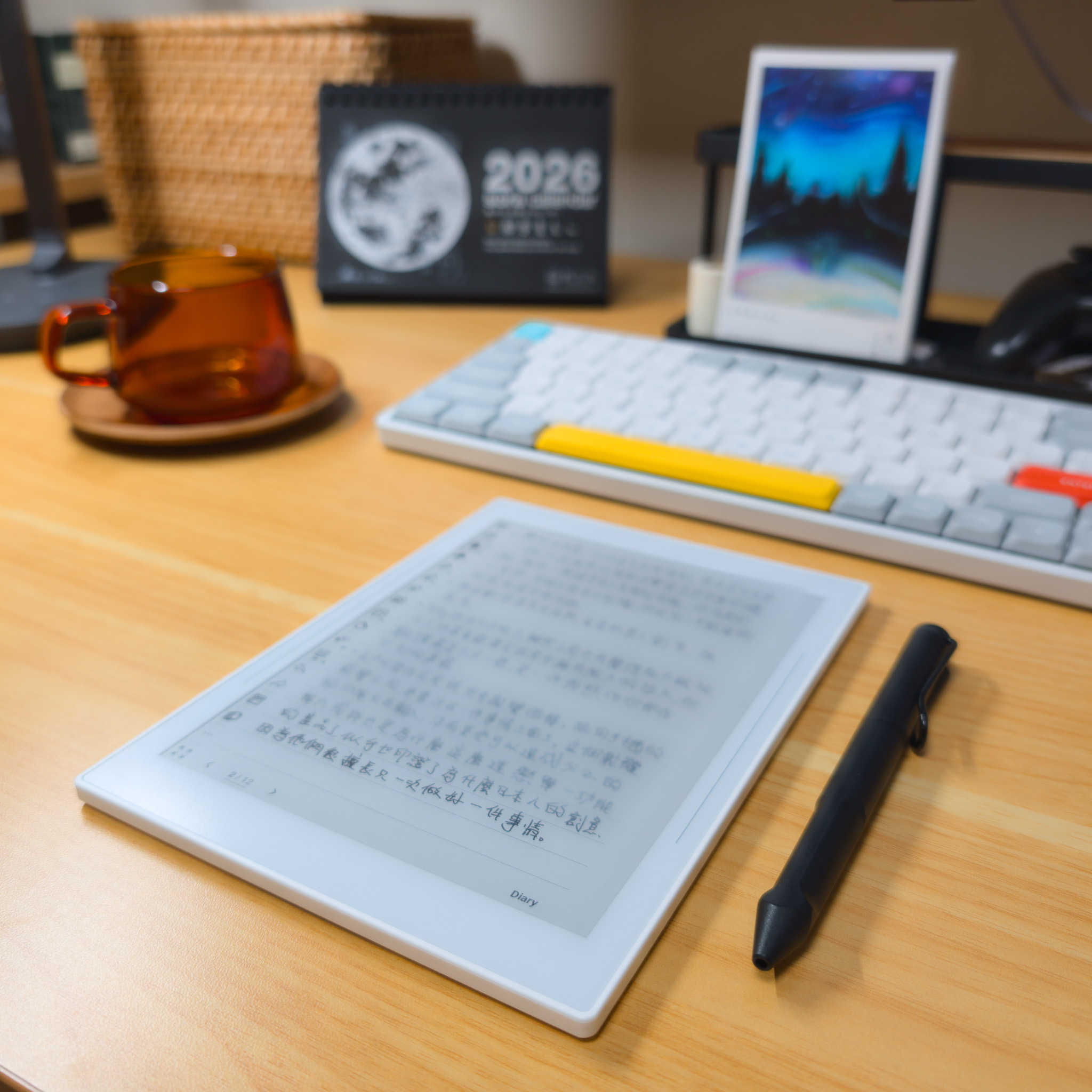

Eventually, I bought a new toy—an e-ink notebook, a product that bridges the digital and the handwritten.

After trying to write daily journals with it for a few weeks, my journal entries have grown longer and longer, as if decades of unwritten weight has slowly seeped in. Of course, I'm someone whose enthusiasm burns bright and fast—whether I can sustain this practice requires long-term observation.

But at least right now, I'm enjoying the feeling of "reclaiming" writing. The continuous flow of handwriting does allow thoughts to be chewed over, organized, and brewed between the lines—different from the rhythmic, punctuated sensation of typing on a keyboard, yet both are different ways of thinking.

Looking back, when I was young, I couldn't find a way to resist. It seemed that "refusal" was the only way out—refusing to write, refusing to speak Taiwanese.

But now that I'm older, I understand it's not a zero-sum game, not the kind of confrontational relationship where one must lose for another to win. Instead, I can find an angle that suits me, positioning myself uniquely among various strengths and weaknesses.

Even though my handwriting is still messy, there are traces of thought between these strokes, which later transform into interesting ideas. In the end, this allows my older self to dissolve the confused emotions of childhood.

And perhaps one day I can also reclaim Taiwanese. I hope when that day comes, it won't be for anyone's criticism or praise, but simply for myself.